The Washington Times

In the 1960s, the country was running out of control — race riots, cities burning, assassinations, campus anarchy. The producers who did the nation’s work and paid its taxes saw their beliefs mocked, their children proselytized and radicalized on campuses where faculties sneered at values they brought with them from home, and where administrators lived in fear of offending New Leftists.

These were the people — solid, productive Americans of both political parties — who would form the nucleus of Richard Nixon’s New Majority . After a close-run win in 1968, that New Majority spoke loudly in 1972, defeating Sen. George McGovern — a good and decent man whose candidacy was captured by the radical left and its loonier fringes — and delivering Nixon, who gave them a voice and a historic 49-state landslide victory.

Before Nixon could engineer that extraordinary realignment, he had to fight his way back from the 1962 loss in the California governor’s race, which seemed to mark the end of his political career, when he told a gleeful press corps they wouldn’t have Dick Nixon to “kick around†any longer. One network ran a special called “The Political Obituary of Richard M. Nixon,†including among its commentators the Soviet spy and perjurer Alger Hiss.

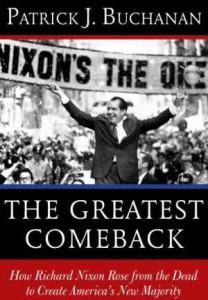

The funeral services were short-lived, however, and the story soon shifted from death to resurrection. The rebirth of Nixon’s political career is the subject of this splendid political memoir by Pat Buchanan, then a young editorial writer for the now-defunct St. Louis Globe-Democrat, who in 1966, convinced that Nixon was going to run again in 1968, told Nixon he’d like to get aboard early. He was flown to New York and hired, bringing the Nixon office staff to three — Rose Mary Woods, Mr. Buchanan, and “Miss Ryan†— “the maiden name of Pat Nixon, the future first lady from whom I used to bum cigarettes,†the author writes.

From that day to the last, Pat Buchanan was joined with Richard Nixon, never wavering in his dedication and total loyalty. From 1966 on, he handled much of Nixon’s correspondence, writing speeches, speech inserts, position papers, editorials, memos (thousands of them, with Mr. Nixon’s handwritten replies, all preserved), conducting opposition research, serving in a variety of positions running from a brief stint as advance man to an even briefer one as press secretary. (He disqualified himself, fearing he’d eventually punch one of the members of what future Vice President Spiro Agnew would call “an effete corps of impudent snobs.â€)

During the last years of the Nixon presidency, when with Aram Bakshian and Ben Stein I shared an office next to Mr. Buchanan‘s, then a senior adviser to the president, we all came to count him a friend and a man to be admired. Dead honest, direct, highly intelligent, focused, knowing exactly who he was, Mr. Buchanan was Nixon’s good right arm from beginning to end. In an appearance at the televised Watergate show trials, straightforward and unapologetic in his testimony, he brought for a day some relief and even a measure of hope to an embattled White House, where the mornings usually began with the latest mortar shell lobbed in by The Washington Post, carrying the latest piece of creative writing from Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. (If the New Journalism was defined as applying fictional techniques to factual reporting, the Woodward-Bernstein version seemed to involve applying journalistic techniques to the writing of fiction.)

Mr. Buchanan also served as Nixon’s ambassador to conservative leaders, such as Bill Buckley and Bill Rusher, and to their followers, who Nixon called “Buckleyites.†After defusing a potential crisis by writing a letter that Rusher called “a masterpiece of broken field running,†Mr. Buchanan was asked by Rusher, “Are you Nixon’s ambassador to the conservatives, or our ambassador to Nixon?†His answer: “The former, always.â€

This is a fast-moving account of those comeback years, written in strong, clear prose, and despite the disaster lying just down the road, surprisingly good-natured, with little or no enmity, except for the most deserving cases, and with an upbeat portrait of Nixon as a surprisingly compassionate man, but a tough politician, energetic and well-informed, with a deep knowledge of world affairs and ideas about how to reset the balance of power and restore America’s international standing, badly damaged by the two preceding administrations.

There are good sketches of key Nixon staffers — Bill Safire, Ray Price, Richard Whalen, Ken Khachigian, Agnes Waldron, Mort Allin, Dwight Chapin; a special tribute to Bill Gavin, who wrote the moving train-whistle section of Nixon’s acceptance speech in Miami; and acknowledgments of the work of political strategists such as Bill Timmons, who made the Nixon campaign a model to be emulated. There’s also an appreciation of the wonderful Nixon family, quoting Norman Mailer’s observation that “a man who could produce daughters like that could not be all bad.â€

In a postscript, Mr. Buchanan writes: “Had Nixon stepped down in January 1973, he would be ranked as one of the great or near-great presidents.†And of that, there could be little doubt, as he demonstrates by enumerating the administration’s singular successes, both domestic and international.

“In all of this,†he writes, “I was there, right from the beginning and right to the end, intimately involved in every battle of Nixon’s White House years,†of which there were many, ending in Watergate and what Mr. Buchanan calls “the first successful coup d’etat in American history.â€

“But all that is the subject, the Lord willing, of another book.â€

That will be a book well worth waiting for.

John R. Coyne Jr., a former White House speechwriter, is co-author of “Strictly Right: William F. Buckley Jr. and the American Conservative Movement†(Wiley).

Read more at: The Washington Times ]]>

The funeral services were short-lived, however, and the story soon shifted from death to resurrection. The rebirth of Nixon’s political career is the subject of this splendid political memoir by Pat Buchanan, then a young editorial writer for the now-defunct St. Louis Globe-Democrat, who in 1966, convinced that Nixon was going to run again in 1968, told Nixon he’d like to get aboard early. He was flown to New York and hired, bringing the Nixon office staff to three — Rose Mary Woods, Mr. Buchanan, and “Miss Ryan†— “the maiden name of Pat Nixon, the future first lady from whom I used to bum cigarettes,†the author writes.

From that day to the last, Pat Buchanan was joined with Richard Nixon, never wavering in his dedication and total loyalty. From 1966 on, he handled much of Nixon’s correspondence, writing speeches, speech inserts, position papers, editorials, memos (thousands of them, with Mr. Nixon’s handwritten replies, all preserved), conducting opposition research, serving in a variety of positions running from a brief stint as advance man to an even briefer one as press secretary. (He disqualified himself, fearing he’d eventually punch one of the members of what future Vice President Spiro Agnew would call “an effete corps of impudent snobs.â€)

During the last years of the Nixon presidency, when with Aram Bakshian and Ben Stein I shared an office next to Mr. Buchanan‘s, then a senior adviser to the president, we all came to count him a friend and a man to be admired. Dead honest, direct, highly intelligent, focused, knowing exactly who he was, Mr. Buchanan was Nixon’s good right arm from beginning to end. In an appearance at the televised Watergate show trials, straightforward and unapologetic in his testimony, he brought for a day some relief and even a measure of hope to an embattled White House, where the mornings usually began with the latest mortar shell lobbed in by The Washington Post, carrying the latest piece of creative writing from Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. (If the New Journalism was defined as applying fictional techniques to factual reporting, the Woodward-Bernstein version seemed to involve applying journalistic techniques to the writing of fiction.)

Mr. Buchanan also served as Nixon’s ambassador to conservative leaders, such as Bill Buckley and Bill Rusher, and to their followers, who Nixon called “Buckleyites.†After defusing a potential crisis by writing a letter that Rusher called “a masterpiece of broken field running,†Mr. Buchanan was asked by Rusher, “Are you Nixon’s ambassador to the conservatives, or our ambassador to Nixon?†His answer: “The former, always.â€

This is a fast-moving account of those comeback years, written in strong, clear prose, and despite the disaster lying just down the road, surprisingly good-natured, with little or no enmity, except for the most deserving cases, and with an upbeat portrait of Nixon as a surprisingly compassionate man, but a tough politician, energetic and well-informed, with a deep knowledge of world affairs and ideas about how to reset the balance of power and restore America’s international standing, badly damaged by the two preceding administrations.

There are good sketches of key Nixon staffers — Bill Safire, Ray Price, Richard Whalen, Ken Khachigian, Agnes Waldron, Mort Allin, Dwight Chapin; a special tribute to Bill Gavin, who wrote the moving train-whistle section of Nixon’s acceptance speech in Miami; and acknowledgments of the work of political strategists such as Bill Timmons, who made the Nixon campaign a model to be emulated. There’s also an appreciation of the wonderful Nixon family, quoting Norman Mailer’s observation that “a man who could produce daughters like that could not be all bad.â€

In a postscript, Mr. Buchanan writes: “Had Nixon stepped down in January 1973, he would be ranked as one of the great or near-great presidents.†And of that, there could be little doubt, as he demonstrates by enumerating the administration’s singular successes, both domestic and international.

“In all of this,†he writes, “I was there, right from the beginning and right to the end, intimately involved in every battle of Nixon’s White House years,†of which there were many, ending in Watergate and what Mr. Buchanan calls “the first successful coup d’etat in American history.â€

“But all that is the subject, the Lord willing, of another book.â€

That will be a book well worth waiting for.

John R. Coyne Jr., a former White House speechwriter, is co-author of “Strictly Right: William F. Buckley Jr. and the American Conservative Movement†(Wiley).

Read more at: The Washington Times ]]>